About Authors:

About Authors:

Dr. BJ Mahendra kumar*1, Jagadish babu D2, Jyothi K2,

*1Professor, Department of Clinical pharmacy,

Sri Adichunchanagiri College of pharmacy, Mandya, Karnataka, India.

2Scholars, Department of Clinical pharmacy,

Sri Adichunchanagiri College of pharmacy, Karnataka,

Mandya, India.

Introduction:

Antibiotics are among the most widely prescribed therapeutic agents among paediatrics patients.1 As we all know, the advantage of therapy with a cephalosporin not only lies in its rather broad spectrum but also in its low toxicity and the drug can be used safely in pregnant women and children. Such therapy can reduce the duration of hospitalization if the susceptible bacterial pathogens have been almost eradicated by a parental cephalosporin and patient’s condition has been brought under control.2 Despite their widespread use in paediatrics, few antibiotics have been studied adequately to be considered safe and effective for use in children. Oral third-generation cephalosporins used commonly in paediatrics include cefixime, cefpodoxime, ceftibuten, and cefdinir.3

[adsense:336x280:8701650588]

Reference Id: PHARMATUTOR-ART-1241

However, the emergence of antimicrobial-resistant organisms demands that the selection of antibiotics be made only after careful evaluation.4 In addition, recent legislation addressing Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved clinical trials will ensure development of information about the use of new medications in children. It is hoped that these trends will reduce the emergence of resistant organisms and lead to more precise use of anti-infective agents for paediatrics.5 The challenge continues: to choose safe and effective antimicrobial agents that are administered to children in a way that maximizes clinical and microbiologic cure, while minimizing adverse drug effects and the development of antibiotic resistance.6 Considering their broad antibacterial spectrum and low frequency of adverse reactions, the third-generation cephalosporins are useful alone or in combination with other antimicrobials for treatment of serious infections in hospitalized patients.7 Prudent use of antibacterial drugs using the appropriate drug at the appropriate dosage and for the appropriate duration is one important means of reducing the selective pressure that helps resistant organisms emerge.8 Long-term monitoring of the susceptibility pattern of clinically important pathogens is, thus, essential for the proper use of antimicrobial therapy in clinical practice.9 It is expected that the present work will be a milestone in the treatment and bring new idea in the field of Paediatrics that will enable the Paediatricians, Physicians, Doctors and Pharmacists for the treatment of common paediatrics bacterial infections and to select the most appropriate antibiotic for patient resulting in least side effects.10

Objectives:

* To study the cephalosporins utilization in hospitalized paediatric patient.

* To assess the usage pattern of cephaloposrins in hospitalized paediatric patients.

* To assess the safety outcome in hospitalized paediatric patient with cephalosporins treatment.

Methodology:

This is a prospective observational study, which assed the current usage pattern of cephalosporin in Hospitalized paediatric Patient. The study was conducted in Department of Paediatric Patient wards in Adichunchanagiri Institute of Medical Sciences, B.G.nagara, Mandya District, and Karnataka, India and duration of study is October – December 2011 and a total 96 patients taken for the study.

Inclusion Criteria

-Paediatric Patients who were hospitalized.

-Patient of either sex aged 0-18years.

-Patient who are prescribed with cephalosporin.

Exclusion Criteria

-Patients prescribed with cephalosporin in out-patient.

-Pregnant women.

Study Procedure:

At enrollement, all the data were pertaining to reason for admission, diagnosis, treatment given, medications used and safety were subjected to analysis in order to assess the usage and safety of cephalosporins in hospitalized paediatric patient. And the microbial investigation was done in paediatrics patients were assessed. Cephalosporin severity was assessed with WHO causality assessment scale and Naranjo’s algorithm; the ADRs were categorized into different causality categories.

[adsense:468x15:2204050025]

Results and discussion:

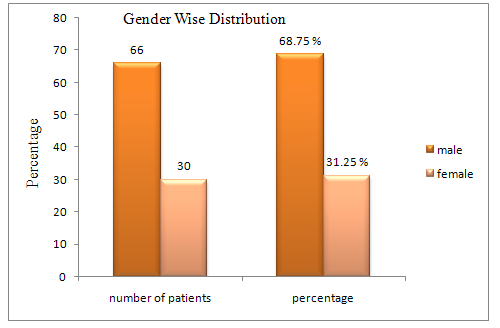

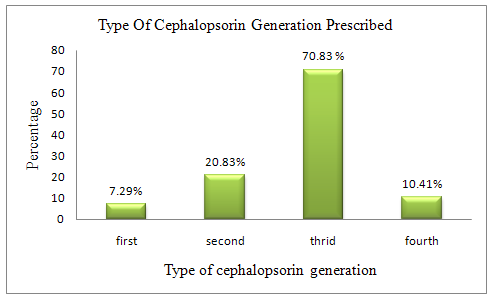

By the prospective observational study male patient were listed more 66(60.22%). Majority of patient in our study belong to age group of 4-8years which is 32.29% of total population. By the collected data it is found that 70.83% of total patient received third generation cephalosporins. The wide usage may be due to their broad spectrum of activity. The most widely prescribed formulation of cephalosporin during the study period was found to be injection (72.91%) due to more bioavailability and absorption. Oral formulations are prescribed for 22.91% of paediatric patients. A high percentage of patients i.e.93% was prescribed at least one antibiotic which was different than study done by Marlies et al i.e. 36 % and Jason Hall i.e. 60.60 %.11

Of the total number of cephalosporins, the most widely prescribed cephalosporin was cefpodoxime+cefuroxime (32.29%) followed by ceftriaxone+cefepime (22.91%) and ceftriaxone+cefpodoxime (21.87%). The most frequently prescribed cephalosporin in paediatric ward was cefpodoxime+cefuroxime. Very few numbers of patients were directed to undergone microbiology investigation 15(15.62%). Only 11.45% of patient received cephalosporin based on recommended therapeutic regimen. In this study most of the patient received prophylactic therapy 35(36.45%) and 20(20.83%) of patient in the study received empirical antibiotic treatment. Prophylactic cephalosporin regimens were most frequently prescribed in Paediatric department. Though being expensive, cephalosporin were used in paediatric ward to a greater extent for prophylaxis due to their excellent board spectrum activity against most of the bacteria causing infection.

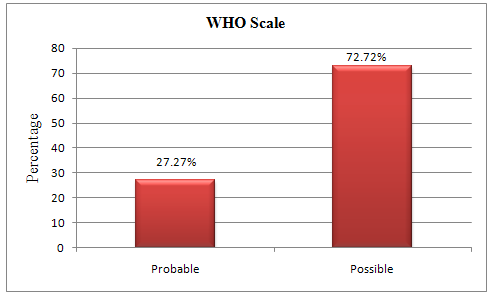

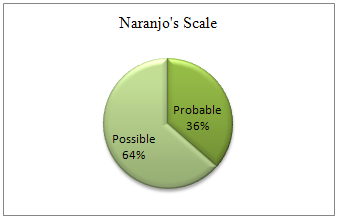

From the study population 11(11.45%) patients developed a total of 11 ADRs. The most common cephalosporin involved in ADR was ceftriaxone 72.72% followed by cefpodoxime, cefadroxil, cefepime (00.09%). Causality assessment between the drug and the reaction was probable in 27.27% (n=3) cases and possible in 72.72 % (n=8) cases by WHO Probability scale where as it is probable in 36.36% (n=4) cases and possible in 63.63% (n=7) cases by Naranjo’sAlgorithm.

Table 1.Gender wise distribution

|

Gender Wise Distribution |

||

|

Gender |

Number Of Patients |

Percentage |

|

Male |

66 |

68.75 |

|

Female |

30 |

31.25 |

Figure 1.Gender Wise Distribution

Table 2.Type of cephalosporin’s generation prescribed

|

Type Of Cephalopsorins Generation Prescribed |

||||

|

Type of generation |

Male |

Female |

Total |

Percentage |

|

First |

06 |

01 |

07 |

07.29% |

|

Second |

10 |

10 |

20 |

20.83% |

|

Third |

50 |

18 |

68 |

70.83% |

|

Fourth |

00 |

01 |

01 |

10.41% |

Figure 2

Table3.Cephalosporin formulation prescribed for paediatric patients:

|

Type of formulation |

Number of patients (%) |

|

Oral |

22(22.91) |

|

Injection |

70(72.91) |

|

Both oral and injection |

04(04.16) |

Table 4.Utilisation of various cephalosporin’s in age wise distribution (n=96)

|

Age in years |

Number of patients |

Type of Cephalosporin |

Percentage |

|

0-4 |

18 |

Cefazolin |

18.75 |

|

4-8 |

31 |

Cefpodoxime+Cefuroxime |

32.29 |

|

8-12 |

06 |

Ceftriaxone+Cefdroxil |

06.25 |

|

12-16 |

21 |

Ceftriaxone+Cefpodoxime |

21.87 |

|

16-18 |

22 |

Ceftriaxone+Cefepime |

22.91 |

Table 5. Microbial investigation on paediatrics patients with cephalosporins

|

Microbial investigation |

Number of patients |

Percentage |

|

Done |

15 |

15.62 |

|

Not Done |

70 |

72.91 |

|

Positive |

11 |

11.45 |

Table 6.Category Based On Cephalosporins Use

|

Antibiotic Use |

Number of Patients |

Percentage |

|

Single |

21 |

21.87 |

|

Combination |

15 |

15.62 |

|

Prophylactic |

35 |

36.45 |

|

Empirical |

20 |

20.83 |

|

Therapeutic |

11 |

11.45 |

Table 7. Cephalosporin Showing ADR

|

Cephalosporin |

Number of ADR |

Percentage(n=11) |

|

Cefpodoxime |

01 |

00.09 |

|

ceftriaxone |

08 |

72.72 |

|

Cefadroxil |

01 |

00.09 |

|

cefepime |

01 |

00.09 |

Table 8. Individual Adverse Drug Reaction

|

ADR |

Number of patients |

Percentage(n=11) |

|

Vomiting |

2 |

18.18 |

|

Diarrhoea |

9 |

81.81 |

Table 9. Causality of ADR WHO Scale

|

Scale |

Percentage |

|

Probable |

3(27.27) |

|

Possible |

8(72.72) |

Figure 3

Table10. Causality of ADR Naranjo’s Scale

|

Scale |

Percentage |

|

Probable |

4(36.36) |

|

Possible |

7(63.63) |

Figure 4

Conclusion:

Of the total 96 paediatric patient reviewed 66(68.75%) were males and 30(31.25%) were females. Majority of the age group of 4-8 years received most cephalosporin. The paediatric patient received prophylactic treatment is 35(36.45%) and empirical treatment is 20(20.83%) and microbial samples were sent to the laboratory in patients 15(15.62%) to determine a bacteriological aetiology of suspected infection and therapeutic treatment was given for 11(11.45%) patients. Most of the hospitalized paediatric patient were received prophylactic treatment is 35(36.45%) and the third generation cephalosporin were prescribed due to their excellent spectrum of activity in the age group 4 to 18 years .it was found that 68(70.83%) of total patient received third generation cephalosporin. The most widely prescribed formulation of cephalosporin is 70(72.91%).at the age between 8-18 years were received ceftriaxone 49(51.04%) as compare to cefpodoxime 52(54.16%) prescribed most frequently. The most common cephalosporin involved was third generation ceftriaxone followed by cefpodoxime, cefadroxil and cefepime. This study shows the wider usage of third generation cephalosporin in hospitalized paediatric patient. Rationale use of cephalosporin will enhance the appropriateness of therapy and treatment, which reduces the resistance of cephalosporin ADR and benefit cost to the paediatric population.

References:

1. Karen L. Bowlware, MD, Terrence Stull, MD. Antibacterial agents in paediatrics. Infect Dis Clin N Am 2004:18; 513–531.

2. Leelarasamee A. New oral cephalopsorins: benefit for community-acquired infection?.J Infect Dis Antimicrob Agents1996 Jan-Apr: 41-42.

3. Bueno SC, Terrence L. Stull TL. Antibacterial Agents in Paediatrics. Infect Dis Clin N Am 2009; 23: 865–80.

4. Kelkar PS and James T. Cephalosporin allergy. N Engl J Med 2001 Sep 13; 345(11): 804-9.

5. Bowlware KL, Stull T. Antibacterial agents in paediatrics. Infect Dis Clin N Am 2004; 18: 513–31.

6. Pong AL, Bradley JS, Guidelines for the Selection of Antibacterial Therapy in Children. Pediatr Clin N Am 2005; 52: 869- 94.

7. Fekety FR. Safety of Parenteral Third-Generation Cephalosporins. A J Med 1990 Apr 9; 88 (suppl 4A):4A-38S-44S.

8. Tenover FC. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria. The American Journal of Medicine. 2006; 119 (6A): S3–S10.

9. Punpanich W, Tantichattanon W, Wongwatcharapaiboon S, Treeratweeraphong V. In Vitro Susceptibility Pattern of Cephalosporin-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria. J Med Assoc Thai 2008; 91 (Suppl 3): S21-7.

10. Ahmed M, Naqvi BS, Shoaib MH, Shaikh D and Hashmi K. Pakistan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2002 Jul; 15(2):13-19.

11. Palikhe N. Prescribing Pattern of Antibiotics in Paediatric Hospital of Kathmandu Valley. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council. 2004 Oct 2; 2(2): 31-36.

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT articles@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE