About Authors:

About Authors:

Sapna Phadtare,* Vaibhav Shinde, Kakasaheb Mahadik

Department of Pharmacognosy, Poona College of Pharmacy,

Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Erandwane,

Maharashtra, Pune-411038

*sapnaphadtare@gmail.com

Abstract

The world is gifted with wonderful and precious resources such as plants, animals and minerals that form the major part of our medical system. We as humans are so dependent on these natural sources that life without them is beyond imagination. Thus it is of prime importance that we look into the conservation and preservation of natural products. The Indian and international government bodies have developed various laws, rules and conventions to ensure sustainability of such natural products. This article reviews the general laws, rules and regulations developed globally for natural and traditional medicine. Various guidelines like WHO, EMEA, TGA guidelines are looked upon. Some difficulties that are faced regarding regulatory issues of herbal medicines are studied. The Acts like Indian patent Act, Plant Variety Protection Act, Farmer’s rights, terms like Biodiversity and Biopiracy are reviewed in this article.

Referene Id: PHARMATUTOR-ART-1697

Introduction

Intellectual property rights (IPRs) are rights to make, use, and sell a new product or technology that are granted, usually for a period of 17- 20 years, solely to the inventor or the corporation which files a claim on the inventor's behalf. IPRs are meant to reward innovators, inventors and researchers. It is a driving force behind rapid industrial growth and progress. Under intellectual property law, owners are granted certain exclusive rights to a variety of intangible assets, such as musical, literary, and artistic works, discoveries and inventions, words, phrases, symbols, and designs. Common types of intellectual property include copyrights, trademarks, patents, industrial design rights and trade secrets in some jurisdictions.Among various kinds of IPRs patents and trademarks are more important to pharmaceutical industries. IPR does not provide protection for inventions that are based on prior existing knowledge.[1] A patent is a set of exclusive rights granted by a state (national government) to an inventor or their assignee for a limited period of time in exchange for a public disclosure of an invention.The association of patents and thievery has a long history. When Columbus sailed out to "discover" a world that was new to him, he was carrying letters patent from the King and Queen of Spain.[2] The procedure for granting patents, the requirements placed on the patentee, and the extent of the exclusive rights vary widely between countries according to national laws and international agreements. Typically, however, a patent application must include one or more claims defining the invention which must be new, inventive, and useful or applicable. In most countries, both natural persons and corporate entities may apply for a patent. The grant and enforcement of patents are governed by national laws, and also by international treaties.[3] Pharmaceutical companies have been making use of traditional knowledge of tribal people to identify plants and their ingredients for developing new medicines. Researchers, screening plants for useful substances can cut down time taken, by getting information from tribal healers on variety of plants used for treating ailments. Many pharmaceutical corporations are misusing traditional knowledge and making huge profits in form of what is known as biopiracy. [4] Trade secret is an IPR which provides simplified protection. It does not require registration with government and is not bound by time. It is useful in countries like India in managing heavy cost of IP protection.[5]

Patents

History Of Indian Patent System [6]

The patent system has been introduced and known in India since 19th century. The first patent act came into effect in the year 1856.It was based on British patent law of 1852.This act granted exclusive rights to inventors for period of 14 years. Later the patent law was amended from time to time.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

A patent can be granted for an invention which may be related to any process or product. The word “Invention “ has been defined under the Patents Act 1970 as amended from time to time.

“An invention means a new product or process involving an inventive step and capable of industrial application.”

According to The Patent Second Amendment Act, 2002, process patents are allowed on microbiological, biochemical and biotechnological processes. Thus, methods of genetic engineering, processes in the pharmaceutical industry using microorganisms and related processes are patentable. The non-patentable aspects of the invention are specified in Patent Second Amendment Act, 2002 This includes plants, animals in whole or any part thereof, including seed varieties and essentially biological processes for the production or propagation of plants and animals. Microorganisms can be claimed for a patent provided; they are not mere discovery of organisms existing in nature. Methods for rendering plants free of diseases or to increase their economic value will be patentable. The Act of 2002 makes it mandatory to deposit the biological material mentioned in the specification with a depositorynotified in the Gazette of India. It is also required that the source and geographical origin of the biological material is disclosed in the specification.[7] In U.S there are three types of patents. These consist of utility patents, design patents, and plant patents. Utility patents are the most common of the three and cover the invention of any new and useful process, composition of matter, machine, or article of manufacture. [8] The plant patents are those covering new plant varieties. But there are some stipulations or conditions with plant patents. Plants that have been bred are acceptable, while plants growing naturally in the wild are not patentable. Plants that are sexually reproduced also do not fulfil the requirement. Only those that are asexually reproduced (i.e., they are reproduced by making a cutting, layering, grafting or inarching) qualify for a patent.[9]

Section 5 Subject to Section 9, a patent may be granted only for an invention in respect of which the following conditions are satisfied:

(1) the invention is new;

(2) involves an inventive step; and

(3) is capable of industrial application

[adsense:468x15:2204050025]

Section 9(1) The following inventions are not protected under this Act:

(1) naturally occurring microorganisms and their components, animals, plants or extracts from animals or plants;

(2) scientific or mathematical rules or theories;

(3) computer programs;

(4) methods of diagnosis, treatment or cure of human and animal diseases;

(5) inventions contrary to public order, morality, health or welfare.[10]

India has established patenting of GMO (Genetically Modified Organisms) including genes of animals and plants. Example: Biotechnology Company Agracetus was granted patent in 1994 that covered all transgenic Soybeans.[11]

TRIPS allows member countries to exclude certain subject matters provided under article 27.3 from patentability which includes essentially biological processes, however member countries can decide on their patentability. Plant patents in US are granted to any persons who invents or discovers and asexually reproduces any distinct and new variety of plants including mutants, hybrids and newly found seedlings other than a tuber, propagated plant or plant found in uncultivated state.[12] Trade secret encourages investment in non-patentable inventions and non-copyrightable works. It provides requisite protection for complex research intensive patent. Trade secrets can protect ethno biological medicinal knowledge also. In case of patent to protect such knowledge requires contributors to reveal a part of knowledge. In case of trade secret need not be revealed.[13]

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT articles@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE

Biodiversity and Biopiracy:

In India, human population is dependent largely on biodiversity. This has generated a rich traditional knowledge and conservation of wild species, and have increased the genetic diversity of agriculturally important plants and animals. The Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers' Rights Act of 2001 (PPVFR) and The Biological Diversity Act of 2002 (BD) are the laws related to biodiversity, introduced in India. There are some loopholes in these laws which is responsible for biopiracy. [14] In June 1992 U.N. Convention was signed by more than 150 countries except U.S.It stated "the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources." [15] The Convention legitimizes a market for owned genes and thereby diminishes biodiversity. In India, for example, peasant producers now cultivate some 50,000 varieties of rice, developed through traditional practices over the millennia. This astonishing variety arose from subtle differences in soil and climatic conditions through mutation, evolution, and the deliberate application of cultural preferences. The GATT-TRIPS rules would prohibit these farmers from harvesting and reusing the seed of any rice variety that has been patented. (Unlike hybrid species cultivated by plant breeders, genetically engineered plants do produce viable seed) Lack of access to seed stocks will cause the abandonment of much of India's biologically diverse agriculture, which in turn sustains healthy diversity in surrounding ecosystems.[16] Conservation of biological diversity and sustainable utilization; regulates access to biological resources through National Biodiversity Authority and through State Biodiversity Boards. It allows free access to biological resources to citizens of India for research; use of bioresources for traditional systems of medicine (Vaidyas & Hakims); Protection of Indigenous knowledge.The property-rights theory states that the rights of disposal of a resource should belong to those who have physical control over the resource. Conventions on biodiversity speak of the same national rights of disposal in the sense of a “national patrimony.” The property rights should belong to the national governments and their local representative institutions for it is their responsibility to plan and manage areas which can be used for to preserve the biodiversity. The incentive of countries of origin to maintain biological resources rises accordingly to the amount of returns these countries get from selling their resources.[17]

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) establishes important principles regarding the protection of biodiversity while recognizing the vast commercial value of the planet's store.The term “biopiracy” was coined in 1993 by Pat Mooney, president of the Rural Advancement Foundation International (RAFI, now the ETC Group), and refers specifically to:“the use of intellectual property systems to legitimize the exclusive ownership and control of biological resources and knowledge, without recognition, compensation or protection for contributions from indigenous and rural communities thus bioprospecting cannot be considered anything but biopiracy.”[18]

The turmeric patent is the stepping stone towards stoppage of biopiracy.US Patent Office revoked the turmeric patent on the basis of a challenge filed by the New Delhi-based Council for Agriculture Research (CSIR). The patent had been granted in March 1995 to two non-resident Indians associated with the University of Mississippi Medical Centre, Jackson, USA. As turmeric has been used for thousands of years for healing wounds and rashes, CSIR challenged the patent on the ground that it lacked novelty. The US Patent Office upheld the objection and cancelled the patent. India is losing the patents of various herbal medicines and formulations to foreigners. eg. Basmati, cumin , gooseberry, blackberry, pepper, soap nut, bitter gourd, brinjal etc.Patents on Neem, Amla, Jar Amla, Anar, Salai, Dudhi, Gulmendhi, Bagbherenda, Karela, Rangoon-ki-bel, Erand, Vilayetishisham, Chamkura all need to be revoked. These patents do not satisfy the criteria of Novelty, Non-obviousness, and Utility. [19] The patents on the anti-diabetic properties of `karela', `jamun', brinjal once again highlight the problem of biopiracy. The use of 'karela', 'jamun' and brinjal for control of diabetes is common knowledge and everyday practice in India. Their use in the treatment of diabetes is documented in authoritative treatises such as the "Wealth of India", the "Compendium of Indian Medicinal Plants" and the "Treatise on Indian Medicinal Plants". This indigenous knowledge and use consists of "prior art". No patent should be given where prior art exists, since patents are supposed to be granted only for new inventions on the basis of novelty and non-obviousness. These criteria establish inventiveness, and patents are exclusive rights granted for inventions. If biopiracy has to stop, then the U.S. patent laws must change, and Article 102 must be redrafted to recognise prior art of other countries. This is especially important given that the U.S. patent laws have been globalised through the TRIPs agreement of the WTO. The European Patent Office (EPO) which administers patents under the European Patent Treaty has acted to revoke a patent granted earlier to a fungicide derived from the Indian medicinal tree, Neem. The challenge to the patent had been made at the Munich office of the EPO by three groups: the EU Parliament's Green Party, Dr. Vandana Shiva of the India-based Research Foundation for Science, Technology and Ecology, and the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements. The three had demanded the invalidation of the patent among others on the ground that the fungicide qualities of the neem and its use has been known in India for over 2000 years, and used to make insect repellents, soaps, cosmetics and contraceptives. In accepting the challenge and revoking the patent, the four-member panel of the EPO at Munich had agreed that the patent amounted to bio-piracy and that the process for which the patent had been granted had been actually in use in India from time immemorial.

Biopiracy Patents Based on Indigenous Knowledge of India

|

COMPANY |

US Patent No. |

Pirated Indigenous |

Reference |

|

'W. R. Grace |

[4556562] [4946681] |

|

[20] |

|

RiceTec Inc. |

[5663484] |

|

" |

|

Sabinsa Corporation |

[5536506] |

Piper nigrum |

? |

|

Calgene |

[5510255] [547991] |

|

? |

|

Calgene |

[5463174] [5563058] |

|

? |

|

Pioneer Hi-hred/DuPont |

[5638637] [5625130] |

|

? |

|

Cromak Research Inc., |

[5900240] |

The anti-diabetic properties of `karela', `jamun',brinjal |

[21] |

Plant Variety Protection Act

The Plant Variety Protection Act Of 1970 (PVPA), gives breeders up to 25 years of exclusive control over new, distinct, uniform, and stable sexually reproduced or tuber propagated plant varieties. In order to be eligible for a certificate under the PVPA, a plant variety must satisfy four requirements. They are, the plant variety must be new, distinct,uniform and stable.[22] The Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Act, 2001 is an act brought into force for the establishment of an effective system for protection of plantvarieties, the rights of farmers and plant breeders and to encourage the development of new varieties of plants.[23] Plant breeders' rights (PBR) only provide a lower level of protection to commercial breeders. TRIPS provide a choice for protecting plant varieties. Most developing countries including India have decided not to have patents for plant varieties and have chosen the sui generis option instead. The sui generis system (translating roughly into self generating) means any system a country decides on, provided it grants effective Plant Breeders’ Rights. The Bill has provisions for researchers’ rights, which allows scientists and breeders to have free access to registered varieties for research. The registered variety can also be used for the purpose of creating other, new varieties. The breeder cannot stop other breeders from using his/her variety to breed new crop varieties except when the registered variety needs to be used repeatedly as a parental line. In that case authorization is required. Therevised UPOV (Union for the Protection of New Plant Varieties)convention extends PBR to cover the reuse. Countries arc now free to extend PBR, to cover the reuse of seed, so that farmers in such a case, cannot use his own seed without paying a royalty to the PBR holder.[24] Any person specified in section 16 may make an application to the Registrar for registration of any variety.

(a) of such genera and species as specified under subsection (2) of section 29; or

(b) which is an extant variety; or

(c) which is a farmers’ variety.

A new variety shall be registered under this act if it conforms to the criteria of novelty, distinctiveness, uniformity and stability.[25]

Farmers’ Rights:

(i) a farmer who has bred or developed a new variety shall be entitled for registration and other protection in like manner as a breeder of a variety under this Act;

(ii) the farmers’ variety shall be entitled for registration if the application contains declaration as specified in clause (h) of sub-section (1) of section 18;

(iii) a farmer who is engaged in the conservation of genetic resources of land races and wild relatives of economic plants and their improvement through selection and preservation shall be entitled in the prescribed manner for recognition and reward from the Gene Fund.

Provided that material so selected and preserved has been used as donors of genes in varieties registrable under this act.

(iv) a farmer shall be deemed to be entitled to save, use, sow, resow, exchange, share or sell his farm produce including seed of a variety protected under this act in the same manner as he was entitled before coming into force of this act provided that the farmer shall not be entitled to sell branded seed of a variety protected under this act.

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT articles@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE

Intellectual Property and Traditional Knowledge:

The traditional medical knowledge of indigenous people throughout the world is being used in the health care system from times immemorial. It has played a crucial role in identifying biological resources worthy of commercial exploitation. Ethno biological data has provided a good way in exploring new pharmaceuticals from nature’s store of biological material. Pharmaceutical, biotechnology and personal care companies have focussed their attention and their advertising, upon plants and animals which have been demonstrated by indigenous people to have beneficial qualities. This has saved those companies at considerable expense in obtaining that knowledge through their own research. In India, traditional medicines are governed by the Drugs and Cosmetics Act of 1940 and the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules of 1945. They regulate the import, manufacture, distribution and sale of drugs and cosmetics. In 1959, the Government of India recognized the traditional Indian systems of medicine and amended the Drugs and Cosmetics Act to include drugs which are derived from traditional Indian medicine. Products under traditional systems are not permitted to be manufactured without a licence. The licence for the same should be obtained from the State Drug Control Authorities. Patent and proprietary medicines derived from the traditional systems must contain ingredients which are mentioned in the recognized books of the traditional systems, as specified in the Drugs and Cosmetics Act. The government is advised by a special committee and an advisory board for Ayurvedic, Siddha and Unani drugs. [26]

To be patentable, an invention has to be novel, or should be an addition to the existing state of relevant technology. Novelty is assessed by reference to the prior art. If it is a published matter then it no more remains novel. A problem with the patent claims of indigenous peoples in relation to traditional medical remedies is that it has been the practice of ethno botanists and ethno pharmacologists to publish accounts of the uses of plants by indigenous people. [27]

The Traditional Medicines Congress (TMC) was formed in the year 2004.The Traditional Medicines Congress (TMC) is proposing federal regulation that will affect everyone involved with herbs. The TMC proposal would violate the intellectual property rights of both cultures and culturally empowered individuals who hold cultural knowledge of medicinal plant use. This violates UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) and WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization) guidelines. [28]

There are two important international conventions that have bearing on intellectual property Rights in indigenous knowledge systems. These are the World Trade Organization’s Trade- Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The CBD is the only major international convention that assigns ownership of biodiversity to indigenous communities and individuals and asserts their right to protect this knowledge.

Two articles of this convention are particularly relevant:

Article 8 (j): State Parties required to “respect, preserve and maintain knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities embodying traditional lifestyles relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity and promote the wider application with the approval and involvement of the holders of such knowledge, innovations and practices and encourage the equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the utilisation of such knowledge, innovations and practices.”

Article 18.4: Contracting Parties should “encourage and develop models of cooperation for the development and use of technologies, including traditional & indigenous technologies." Intellectual property rights are basically a mechanism to allocate ownership of knowledge and distribute benefits from it among competing claimants. The incorporation of indigenous knowledges into the system of patents and copyrights strengthens the material forces that have depleted the resources and the strength of indigenous peoples. If herbal medicines are patented - either domestically or internationally – the medicines used as the first and last resort for healthcare by the poor may become unaffordable. In countries with patents, the medicines are more expensive.[29]

IPR are inadequate and inappropriate for protection of traditional ecological knowledge and community resources because they:

- recognize individual, not collective rights;

- require a specific act of “invention”;

- simplify ownership regimes;

- stimulate commercialization;

- recognize only market values;

- are subject to economic powers and manipulation;

- are difficult to monitor and enforce;

- are expensive, complicated, time-consuming. [30]

The TRR concept was first elaborated in an article By Posey entitled: “Traditional Resource Rights: De Facto Self-determination for Indigenous Peoples,” (TRIPs, 1994) and it has been proposed as a specific example of a sui generis system of legal rights. describes the many “bundles” of rights existing and being developed which can be utilised for the protection of and compensation for the use of traditional knowledge and resources. Traditional resources include plants, animals, and other material objects, like minerals and cultural artifacts, which may have intangible (e.g. sacred, ceremonial, heritage or aesthetic) qualities. The TRR concept can form the basis for sui generis systems for protection and benefit-sharing. Traditional Resource Rights consists of the following bundles of rights, which are supported by the legally and non-legally binding agreements, Land and territorial rights, Right to religious freedom, Right to development, the right to privacy, Prior informed consent. Environmental integrity, Intellectual property rights, Right to protection of cultural, Heritage, Recognition of cultural landscape, Recognition of customary law and practice, Farmers’ Rights.[31]

The Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999

It is an act to provide for registration and better protection of geographical indications relating to goods. This act extends to whole of India. Goods mean any agricultural, natural or manufactured goods or any goods of handicrafts or of industry and include food stuff. Indication includes any name, geographical or figurative representation or any combination of them conveying or suggesting the geographical origin of goods to which it applies.[32] The Registrar of Geographical Indications shall maintain a Register of Geographical Indications Agents wherein shall be entered the name, address of the place of residence, address of the principal place of business, the nationality, qualifications and date of registration of every registered Geographical Indications Agent.[33] Some products are unique because they can be produced only in a certain geographical region and they become reputed because they have certain quality traits like in the case of Champagne or Basmati rice. The important issue about these products is the link between their quality characteristics and the geographical attributes of the region where these products are being produced. Such products are mostly agricultural commodities like wine, cheese, rice, fruits, and coffee but also refer to handicraft items such as silk clothes with traditional paintings on them; or it could be even herbal medicines such as Neem and Turmeric. Property rights are often sought for such goods based on the fact that they are produced in a geographical region which has unique geo-climatic characteristics and uses traditional skills. These render a unique value to the product and make replication of these goods elsewhere impossible.

GIs registered in India during 2003 - 08 [34]

Mysore sandalwood oil, Coorg Orange ,Kangra Tea, Spices-Alleppey Green Cardamom, Coorg Green Cardamom, Monsooned Malabar Robusta Coffee.

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT articles@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE

Main difficulties regarding regulatory issues for herbal medicines

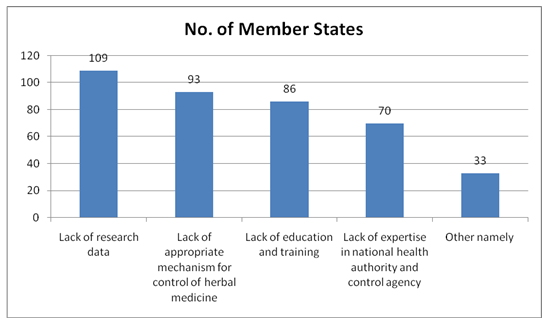

The countries were asked about their specific needs and given the opportunity to provide feedback on the types of support they most needed from WHO. The first question was asked about the main difficulties faced by each Member State regarding regulatory issues for herbal medicines. The options, the countries could select as their answer, included the following: lack of research data, lack of expertise within the national health authorities and drug control agency, lack of appropriate mechanisms for control of herbal medicines, lack of education and training.

Main difficulties regarding regulatory issues for herbal medicines[35]

Regulatory Guidelines and Herbal medicines

Herbal medicines, have been increasingly used worldwide during the last two decades. Unfortunately, the number of reports of patients experiencing negative health consequences caused by the use of herbal medicines has also been increasing. One of the major causes of reported adverse events is directly linked to the poor quality of herbal medicines, including raw medicinal plant materials.The legal process of regulation and legislation of herbal medicines changes from country to country. The reason for this involves mainly cultural aspects and also the fact that herbal medicines are rarely studied scientifically.

WHO Guidelines:

WHO has developed a series of technical guidelines relating to the quality control of herbal medicines of which these WHO guidelines on good agricultural and collection practices (GACP) for medicinal plants are the latest. The guidelines are divided into five sections: section 1 provides a general introduction, sections 2 and 3 discuss good agricultural practices for medicinal plants and good collection practices for medicinal plants, respectively. Section 4 outlines common technical aspects of good agricultural practices for medicinal plants and good collection practices for medicinal plants, while section 5 considers other relevant issues. WHO guidelines gives good agricultural practices for medicinal plants including selection of medicinal plants, seeds and other propagation materials, cultivation, site selection, ecological environment and social impact, climate, irrigation and drainage soil, plant maintenance and protection, harvest, personnel, good collection practices for medicinal plants includes permission to collect, selection of medicinal plants for collection, technical planning, collection and personnel.Common technical aspects of good agricultural practices for medicinal plants includes post-harvest processing, bulk packaging and labelling, storage and transportation, equipment, quality assurance, documentation, personnel. Some of the other relevant issues includes ethical and legal considerations, Intellectual property rights and benefits-sharing, threatened and endangered species. Guidelines to carry out the standardization of crude as well as finished herbal products are also provided by WHO.

EMEA Guidelines:

This EMEA guidelines describes the general principles for determining and justifying uniform specifications for herbal starting materials and herbal medicinal products.The declaration guideline does not include requirements for declarations on the labelling of medicinal products. However, the EMEA Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC) has decided to prepare an annex for the guideline, specifically describing any special rules applicable to labelling (labels and patient information leaflets).[36] EMEA provides guidelineon allergen products, its production and quality. [37] Before the European Commission, and the EMEA / HMPC became the key players for the regulation of the herbal market, there has been other organisations facing the acclamation of diverse national situations. This refers mainly to the European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines (EDQM) with the Commission of the European Pharmacopoeia (Ph Eur) in Strasbourg. The Good Agricultural Practice guideline for herbal starting materials, for instance has been built on guidelines from the EUROPAM (The European Herb Growers Association, first version 1998), and the WWF Traffic network, starting together with other organisations in 1993 with the Guidelines on the Conservation of Medicinal Plants. [38]

TGA Guidelines:

Traditional use, in relation to a designated active ingredient, means use of the designated active ingredient that:

(a) is well documented, or otherwise established, according to the accumulated experience of many traditional health care practitioners over an extended period of time; and

(b) accords with well-established procedures of preparation, application and dosage.[39]

The TGA does not require general microbial limits for raw materials. The only stipulation is that the finished products that contain these raw materials must comply with the TGA Guidelines. The types of materials which would be classified as being of natural originand which would cause products containing them to be classified Category 3b (BP/Ph Eur) or 2b are raw plant materials or animal material which has not been fully processed. Topical products should normally comply with the limits in Category 1a of the TGA guidelines or Category 1b if they contain antiseptics or corticosteroids.[40]

The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) is responsible for administering the provisions of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (the Act). TGA maintains the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods. Medicines that are assessed to be of higher risk are individually evaluated for safety, quality and efficacy before they can be released onto the market. If after evaluation, a higher risk medicine is approved by the TGA for use, it is included on the ARTG as a Registered medicine. Registered medicines include both prescription medicines and non-prescription medicines. The TGA’s Approved Terminology for Medicines classifies herbal ingredients as ‘herbal substances’. Herbal substances are preparations of plants and other organisms that are treated as plants in the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature, such as fungi and blue-green algae. The definition of a ‘herbal substance’ in the regulations includes details of acceptable production processes. In a regulatory context, ‘herbal substance’ is referred to in Schedule 4 of the Regulations[41]

Australian regulatory guidelines for complementary medicines (ARGCM):

The ARGCM is structured in five parts.

- Part I provides guidance on the Registration of complementary medicines.

- Part II provides guidance on Listed complementary medicines.

- Part III provides guidance on the evaluation of complementary medicine substances for use in Listed medicines (that is, for inclusion in Schedule 4 of the Therapeutic Goods Regulations 1990) including new substances, 'switch' substances1 and excipients used in complementary medicines.

- Part IV provides general guidance in relation to complementary medicine modalities such as homoeopathy, traditional herbal medicine and aromatherapy. This part also provides information on exempt medicines, combination complementary / pharmaceutical medicines and the food / medicine interface and contains a glossary of terms.

- Part V provides details of TGA policy guidelines relevant to complementary medicines.

This Part provides guidance to applicants submitting applications for the Registration of complementary medicines. The regulatory requirements for listed medicines are discussed in Part II of these guidelines, and those for the evaluation of complementary medicine substances are discussed in Part III.

The evaluation of an application for Registration of a complementary medicine will include:

1. an assessment of the safety, quality and efficacy of the product; and

2. an assessment of the safety and quality of any new substances that are in the product.

Herbal Medicines and EU Directive

Herbal medicines are assuming large use in the primary healthcare of individuals and communities. The interest in traditional and alternative systems of medicine in many developed countries is progressively increasing with time. Consumer surveys show a positive public attitude to complementary medicine. The regulation of herbal medicines is characterized by large differences depending on the ethnological, medical, and historical background of each country. [42]

Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products Directive by EU was introduced on 31 march 2004.Under this regulation, all herbal medicinal products are required to obtain an authorization to market within the EU.In 2000 the House of Lords selected a committee on Complementary and Alternative Therapies. They suggested three areas need regulation, the first of which included herbal medicine, the second area included the complement conventional medicines which don’t proffer diagnosis, example Aromatherapy and the third area included Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese medicine.[43] Directives are only binding on the member states to whom they are addressed, which can be just one member state or a group of them.[44] Under the Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products Directive, a company needs to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of the herbal medicine through traditional use within the EU for at least 30 years or 15 years within the EU and 30 years outside the EU. There are eligibility criteria for a herbal medicine to qualify under this legislation.

- Only herbal medicines that are administered orally, externally, or by inhalation are suitable. Any medication that requires intravenous administration will not be authorized.

- Only herbal medicines that are intended to be used without supervision by a medical doctor will be authorized by this scheme.

- The intended use of a herbal medicines will only be authorized on the basis of its traditional history and/or the recognized pharmacological properties of the herbal ingredient(s).

- Vitamins and minerals may be added to the herbal medicine provided that their use is ancillary to the herbal ingredient(s)

- If the competent EU member judges that the herbal medicine fulfills the criteria for a marketing authorization, then an authorization under Traditional Herbal Medicines Product Directive should not be granted.

Herbal medicine products manufactured using isolated active ingredients from plants will not be regarded as herbal medicines and will not receive an authorization under this scheme. [45] The EU Directive on Food Supplements(FSD) passed into European law in July 2002.It effectively brought about a ban on 300 nutrients included in 5,000 health products, most of which are in dietary supplements closest to food forms. The EU Commission has designated a list of permissible nutrients called 'The Positive List.' Specialist vitamin manufactures have expressed concern that their products containing organic ingredients, excluded from the 'List', are being compromised by synthetic or inorganic equivalents that are on the 'List.' All attempts to include a number of organic vitamins and minerals have been refused. [46] European Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products Directive (THMPD). This directive comes from the EU, now UK law, and comes into full force in April 2011. It is set to take the place of Section 12(2) of the 1968 Medicines Act. This states that all "over-the-counter" herbal medicines sold in shops must have a Traditional Medicines License by 2011. This would significantly add to the prices of "over-the-counter" herbal medicines, probably at least doubling them, as producers are forced to pay the new product licence fees.[47] The Herbal Directive permits registration of traditional herbal medicinal products that also contain vitamins and minerals, provided their action is ancillary to the active ingredient and only where proven safe. This potentially covers several products currently sold as dietary supplements.

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT articles@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE

MHRA and Herbal medicines:

In a recent report, 77% of adults agreed it is important that herbal medicines are regulated. Features of regulation that British adults feel are particularly important include: a check that ingredients are safe before the product is allowed to be sold (83% of all adults saying this is either ‘essential’ or ‘very important’). Some herbal medicines are indeed regulated by the MHRA, and meet assured safety standards. These are licensed and have a PL (Product License) number on their labels. In 2005, the MHRA also launched a new registration scheme for herbal medicines - the Traditional Herbal Registration Scheme (THR) - under which herbal medicines have to be made to specific standards of safety and quality. These products have a THR number on their labels. A herbal remedy without a PL or THR number on its label is unlicensed and has not been assessed by the MHRA, therefore nothing is known about its safety, quality, or any potential side effects.[48]

MHRA Public Perceptions of Herbal Medicines:

Results are based on 2,032 face-to-face interviews (all bases quoted here are unweighted).

- Data have been weighted to age, gender, work status, area, ethnicity and tenure.

- Fieldwork between 5th – 11th September 2008.

- Where results do not sum to 100, this may be due to multiple responses, computer rounding or the exclusion of don’t knows/not stated.

Total seventeen questions were asked about herbal medicines which gave an overall idea of usage and understanding about herbal medicines among the people.[49]

Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994:

On the basis of this law, herbal medicines are not evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration and, most important, these products are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent diseases.[50] The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) regulate dietary supplement labelling, advertising, and marketing. The FDA assumes primary responsibility for food and supplement product labelling, while the FTC regulates food and supplement advertising and marketing. For dietary supplements, the most significant amendment to the FDCA is the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994. DSHEA defines dietary supplements as products (“other than tobacco”) that are intended to supplement the diet, and contain a “dietary ingredient.” The dietary ingredient can be a vitamin, mineral, herb, amino acid, a substance used to increase total dietary intake (e.g., an enzyme), concentrate, metabolite, constituent, or extract. 51 A major difference between a drug and a dietary supplement is that dietary supplements may 21 not claim to “diagnose, cure, mitigate, treat, or prevent illness.” 7 It is interesting to note that dietary supplement manufacturers are allowed to make certain “structure/function” claims, which are often vaguely worded claims of health benefits. 52 DSHEA established federal product labelling guidelines for dietary supplements and instructed the FDA to issue regulations specifying detailed requirements. The information that must be disclosed on every dietary supplement label includes: serving size; directions for use; net quantity of contents; dietary ingredients that have a Reference Daily Intake (RDI) or Daily Reference Value (DRV), as well as ingredients for which RDIs and DRVs. have not been established; botanical ingredients; proprietary blends; and nutrients required in the labelling of conventional foods. DSHEA allows manufacturers to describe a dietary supplement’s effect on the “structure or function” of the body or the “well being” achieved by consuming the dietary ingredient. DSHEA empowered the FDA to issue current good manufacturing practices (GMPs) for the dietary supplement industry. With respect to methodology issues, FDA is not persuaded that herbal products should be exempt from labelling until analytical methodology is validated for all herbal products. FDA is aware of the difficulties in adapting analytical methods. 53

Conclusion

From the above article, we get an overview of various rules, laws and acts regulating the sustainable use of herbal medicines and other natural products. It gives an idea about their role in conservation of these natural resources. Also the member states should provide their valuable feedback about the problems faced by them as well as support required by them in maintaining the quality of herbal medicines with assistance of the guidelines developed for the same. Thus these laws should be made stronger and efficacious so that we can stop biopiracy and unethical use of traditional knowledge and medicine.

References:

1 http://www.netlink.de/gen/biopiracy.html (24th Oct 2009).

2 http://www.greens.org/s-r/15/15-14.html (24th Oct 2008).

3 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patent (26th Oct 2008).

4 Venkatraman K, Intellectual Property Rights,Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity of India, Journal of Intellectual Property Rights,13(2008)326-335.

5 Kumar A, Towards patentability of essentially biological processes, Journal of Intellectual Property Rights, 23 (2008)129-138.

6 http://www.patentoffice.nic.in/ipr/patent/patents.htm (27th Oct 2008).

7 Sahai S, Special section: Transgenic crops, Current Science, 3(2003) 84.

8 http://www.patentlawportal.com/information/patentbasics/what-is-patent-law.html (27th Oct 2008).

9 http://www.patentlawportal.com/information/patentbasics/what-types-of-patents-are- available.html (27th Oct 2008).

10 http://www.ecapproject.org/fileadmin/ecapII/pdf/en/information/thailand/patent_act_ 2522 pdf (27th Oct 2008).

11 Venkatraman K, Intellectual Property Rights, Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity of India, Journal of Intellectual Property Rights,13(2008)326-335.

12 Kumar A, Towards patentability of essentially biological processes, Journal of Intellectual Property Rights, 23(2008)129-138. 13 Harshwardhan, Keshri S, Trade secrets: A secret still to unveil, Journal of Intellectual Property Rights,13(2008)208-217.

14 http://www.scidev.net/en/agriculture-and-environment/biodiversity/opinions/holes-in- indian-laws-promote-biopiracy.html 1 SciDev.Net (28th Oct 2008)

15 http://www.netlink.de/gen/biopiracy.html (2nd Nov 2008).

16 Navdanya. Cultivating Diversity. Research Foundation for Science, Technology and Natural Resource Policy. Delhi, India. 1993.

17 Lerch A, Property Rights and Biodiversity, European Journal of Law Economics, 6(1988)285–304.

18 Carlo G, BiopiÒacy and Intellectual Property as the Basis for Biotechnological Development: The Case of Mexico Delgadoy, International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society ,16 (2002)299.

19 http://www.twnside.org.sg/title/tur-cn.htm (2nd Nov 2008). 20 http://www.greens.org/s-r/15/15-14.html (2nd Nov 2008).

21 http://www.organicconsumers.org/Patent/uspatsys.cfm (27th Oct 2008).

22 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plant_Variety_Protection_Act_of_1970 (4th Nov 2008).

23 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plant_Variety_Protection_Act_of_1970 (4th Nov 2008).

24 http://www.molecular-plant-biotechnology.info/patenting-of-biological- material/plantbreeders-rights.htm (1st Nov 2008).

25 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plant_Variety_Protection_Act_of_1970(4thNov 2008).

26 http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jwhozip57e/4.5.html (2nd Nov 2008).

27 http://193.5.93.80/edocs/mdocs/tk/en/wipo_iptk_rt_99/wipo_iptk_rt_99_3.doc (2nd Nov 2008).

28 http://www.traditionalmedicines.info/ (6th Nov 2008).

29 http://www.codesria.org/Links/conferences/general_assembly11/papers/ngetich.pdf(1st Dec 2008)

30 Arihan O, Özkan A M, Traditional Medicine And Intellectual Property Rights, Journal of Faculty of Pharmacy of Ankara, 36 (2) (2007) 135 - 151.

31 Craig D, Impacts On Indigenous And Local Communities, An Example Of Integrated Rights Approaches: Traditional Resource Rights And S U I Generis Systems, 93-95.

32 http://ipindia.nic.in/girindia/GI_Act.pdf (6th Nov 2008).

33 http://www.patentoffice.nic.in/ipr/gi/Girule~1.PDF (6th Nov 2008).

34 http://www.pegnet.ifw-kiel.de/activities/pradyot.pdf (6th Nov 2008).

35 http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js7916e/8.html (7th Nov 2008).

36 http://www.dkma.dk/1024/visUKLSArtikel.asp?artikelID=13462(7th Nov 2008).

37 http://www.tga.gov.au/DOCS/pdf/euguide/bwp/30483107en.pdf (9th Nov 2008).

38 Peschel W, The Traditional Herbal Medicines European Directive, Boletin latinoamericano y del caribe de plantas medicinales y aromaticas, 6 (4) (2007)104-105.

39http://www.comlaw.gov.au/ComLaw/Legislation/ActCompilation1.nsf/0/840CB0162B421 (1st Nov 2008).

40 http://www.tga.gov.au/pmeds/argpmap17.pdf (1st Nov 2008).

41 http://www.anztpa.org/cm/herbal.pdf (3rd Nov 2008)

42 Benzi G, Herbal medicines in European regulation Ceci A, Pharmacological Research, (35(5)1997)355-362.

43 Dawson W, Herbal Medicines and the EU Directive, The Journal of Royal College of Physicians of Edinburg, 35(2005)25-27. 44 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Directive_(European_Union) (10th Nov 2008). 45 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Directive_on_Traditional_Herbal_Medicinal_Produ cts (10th Nov 2008).

46 http://www.i-sis.org.uk/vitamins2.php (10th Nov 2008).

47 http://www.nimh.org.uk/uploads/857_Original%20+%20AV%20060308.doc (10th Nov 2008).

48http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/Generalsafetyinformationandadvice/Advicean dinformationforconsumers/Usingherbalmedicines/CON019609 (11th Nov 2008).

49 http://www.ipsos-mori.com/Assets/Docs/Polls/public-perceptions-of-herbal-medicines- topline.pdf (11th Nov 2008).

50 Calixto J B, Efficacy, safety, quality control, marketing and regulatory guidelines for herbal medicines (phytotherapeutic agents), Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 33(2000)2.

51 Gilhooley M, “Deregulation and the Administrative Role: Looking at Dietary Supplements,” Mont Law Rev,62(2001)85- 96.

52 Bent S, Herbal Medicine in the United States: Review of Efficacy, Safety, and Regulation, Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(6) (2008) 854-859.

53 Rules and Regulations Federal Register, 62( 184)(1997)49829.