About Authors:

About Authors:

Kapil Sharma*, Priyanka Sharma**

*M.Pharm, Yaresun Pharmaceutical Pvt Ltd, India

**M.Sc, Yaresun Pharmaceutical Pvt Ltd,

Rajasthan, India.

1.PELLETS

Pellets are spheres of varying diameter depending on the application and the wish of the producer. Applications are found not only in the pharmaceutical industry but also in the agribusiness (e.g., fertilizer, fish food) and in the polymer industry.

In the pharmaceutical industry, Pellets can be defined as small, free-flowing, spherical particulates manufactured by the agglomeration of fine powders or granules of drug substances and excipients using appropriate processing equipment. The term also has been used to describe small rods with aspect ratios of close to unity.

Traditionally, the word pellet has been used to describe a variety of systematically produced geometrically defined agglomerates obtained from diverse starting materials utilizing different processing conditions. Pellets for pharmaceutical purposes are usually produced in the size range of 0.5 to 1.5 mm. The final oral multiple-unit dosage form can be either a hard gelatin capsule filled with pellets or a tablet composed of carefully compressed pellets. Pellets are prepared using different technologies such as layering of the drug solution, suspension or powder on the inactive cores, extrusion/spheronization, and agglomeration in rotogranulators or rotoprocessors, compression, spray drying, or spray congealing.

[adsense:336x280:8701650588]

REFERENCE ID: PHARMATUTOR-ART-1261

1.1Advantages and Applications

i. Flexibility in dosage form design and development

ii. It permits the combination of different release rates of the same drug in a single dosage form

iii. Controlled release technology

iv. Disperse freely in the GI & invariably maximize drug absorption

v. Reduce peak plasma fluctuation

vi. Minimize potential side effects without lowering bioavailability

vii. Avoiding high local concentration

viii. Less susceptible to dose dumping

ix. Reduce gastric emptying rates so minimize inter and intra subject variability of plasma profile

x. Pellets have a low surface area to volume ratio and provide an ideal shape for the application of film coatings

xi. Reproducible fill weights in capsules

xii. Can be used to mix incompatible drugs

|

Brand |

Generic |

Delivery Technology |

Manufacturer |

|

Omez |

Omeprazole |

Delayed-release pellet system |

Dr. Reddy’s |

|

Cardizem CD 360mg |

Diltiazem |

Once-daily pellets system |

Aventis |

|

Isorythm |

Disopyramide |

Slow-release pellets system |

Merck Lipha |

|

Duranitrat |

Isosorbide dinitrate |

Slow-release pellets system |

Merck Generika |

|

Loxen |

Nicardipine |

Slow-release pellets system |

Sandoz-Novartis |

|

Diesis |

Isosorbide mononitrate |

Slow-release pellets system |

Sanofi-Synthélabo |

Table 1. Some examples of marketed pellets formulations.

[adsense:468x15:2204050025]

2. Pellet Formation and Kinetics

Fine powders can readily be formed into agglomerates by the introduction of a liquid phase followed by suitable agitation or tumbling. The liquid and solid phases are brought into close contact; this allows binding forces to develop and bring about agglomeration. Growth of the particles occurs either by collisions and successful adherence of primary feed particles onto which particles collide and attachés themselves. This result in pellet growth formation.

When two particles come into close contact, the cohesive forces that hold the particles together are:

i. Intermolecular attractive forces: these are very short range attractions, active up to a maximum of 103 ?. on the whole, van der Walls dispersive forces makes the most significant contribution.

ii. Electrostatic attractive forces: these are almost always present in particulate systems. They are produced primarily by inter-particle friction. Although these forces are generally less than those experienced in other binding mechanisms, the net effect is to hold or orient particles in a contact region for sufficiently long for other, more dominant mechanism to operate.

iii. Liquid bridge modes: these are three physical situations in which the amount of liquid present produces cohesive forces between particles. The contributing mechanisms are adsorbed liquid layers, mobile liquid bridges, and viscous or adhesive binders. Once sufficient liquid is present to produce liquid bridges in an assembly of particles, the cohesive strength of the material increased.

Beyond this nucleation phenomenon, the change in size can occur by a number of mechanisms. The prevailing mechanisms depend on factors such as the solid properties, liquid properties, and mode of operation. After nucleation has occurred, the predominating growth mechanisms are; (i) coalescence, and (ii) layering of either feed particles or fines from the breakdown of established agglomerates.

Binders can contribute significantly to agglomerate strength. Binders are additives that impart cohesive properties to the powdered materials through particle-particle bonding. Apart from imparting strength to pellets, binders also improves the flow properties by appropriate formulation of the pellets with the desired pellet size and hardness.

2.1 Techniques of Pelletization

Pelletization is an agglomeration process that converts fine powders or granules of bulk drugs and excipients into small, free-flowing, spherical or semi-spherical units, referred to as pellets. Generally of size range 0.5-1.5 mm.

2.1 Powder Layering

Powder layering involves the deposition of successive layers of dry powder of drug or excipients or both on preformed nuclei or cores with the help of a binding liquid. Because powder layering involves the simultaneous application of the binding liquid and dry powder, it generally requires specialized equipment. The primary equipment-related requirement in a powder-layering process is that the product container should have solid walls with no perforations to avoid powder loss beneath the product chamber before the powder is picked up by the wet mass of pellets that is being layered on.

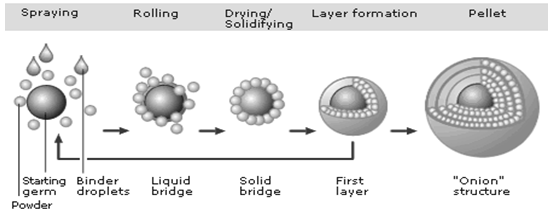

Figure 2.1 Powder layering process.

The first equipment used to manufacture pellets on a commercial scale was the conventional coating pan, a machine that has been used by pharmaceutical firms, primarily for sugar coating, for a long time. The conventional coating pan became the first pharmaceutical equipment used not only to manufacture nonpareils but also to develop sustained-release products of a number of prescription drugs using non-pareils as starter seeds. Conventional coating pans, however, have had significant limitations as pelletization equipment. The degree of mixing is very poor, and the drying process is not efficient. Mixing is a function of the pan shape, the tilt angle, the baffle arrangement, and the rotational speed of the pan itself. These parameters must be optimized to provide uniform drying and sufficient particle movement to eliminate the potential formation of dead spots during the operation and to maximize yield.

During powder layering, a binding solution and a finely milled powder are added simultaneously to a bed of starter seeds at a controlled rate. In the initial stages, the drug particles are bound to the starter seeds and subsequently to the forming pellets with the help of liquid bridges originated from the sprayed liquid. These liquid bridges are eventually replaced by solid bridges derived either from a binder in the application medium or from any material, including the drug substance, that is soluble in the liquid. Successive layering of the drug and binder solution continues until the desired pellet size is reached. Throughout the process, it is extremely important to deliver the powder accurately at a predetermined rate and in a manner that maintains equilibrium between the binder liquid application rate and the powder delivery rate. If the powder delivery rate is not maintained at predetermined equilibrium levels, over-wetting or dust generation may occur, and neither the quality nor the yield of the product can be maximized.

Pieces of equipment that overcame the limitations of coating pans and revolutionized powder-layering processing as a pelletization technique are tangential spray or centrifugal fluid-bed granulators. Although tangential spray equipment was originally developed to perform granulation processes, its application was later expanded to cover other unit operations including the manufacture and coating of pellets.

Micronizing or finely milling the drug before layering improves the efficiency of the layering process significantly and provides morphologically smooth pellets that are suitable for film coating. However, in the majority of cases, Micronisation tends to impact flow and thus the delivery rate, a critical process parameter. Therefore, it is likely that during processing, powders may adhere to the sides of the hopper or the feed screw and may even form rat holes within the hopper. To improve the flow properties of the drug substance, glidants are incorporated into the powder before processing. Chemically, glidants could be hydrophobic or hydrophilic and are chosen based on the type of formulation selected.

Finally, the rheological properties of the binding liquid, the liquid application rate, and drying air temperature should be optimized to produce the desired product temperature. In addition, the powder should be delivered at a rate that maintains a balance between the surface wetness of the cores and powder adhesion.

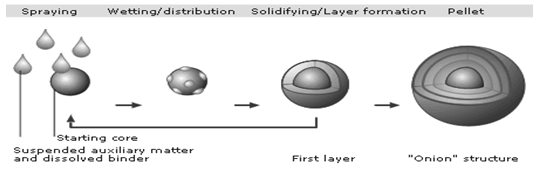

2.2 Solution/Suspension Layering

During processing, all the components of the formulation are first dissolved or suspended in an appropriate quantity of application medium to provide a formulation with the desired viscosity and is then sprayed onto the product bed. The sprayed droplets immediately impinge on the starter seeds and spread evenly on the surface, provided the drying conditions and fluid dynamics are favorable. This is followed by a drying phase that renders dissolved materials to precipitate and form solid bridges that would hold the formulation components together as successive layers on the starter seeds. The process continues until the desired quantity of drug substance and thus the target potency of the pellets are achieved.

Figure 2.2 Solution/suspension layering.

2.3 Extrusion-Spheronization

Extrusion–spheronization is a multistep process involving a number of unit operations and equipment. However, the most critical pieces of processing equipment that, in effect, dictate the outcome of the overall process are the extruders and the spheronizers.

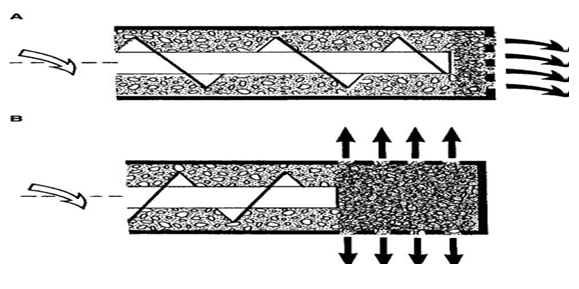

A variety of extruders, which differ in design features and operational principles, are currently in the market and can be classified as screw-fed extruders, gravity-fed extruders, and ram extruders. Screw-fed extruders have screws that rotate along the horizontal axis and hence transport the material horizontally; they may be axial or radial screw extruders (Fig.3). Axial extruders, which have a die plate that is positioned axially, consist of a feeding zone, a compression zone, and an extrusion zone. The product temperature is controlled during extrusion by jacketed barrels. In radial extruders, the transport zone is short, and the material is extruded radially through screens mounted around the horizontal axis of the screws.

Figure 2.3.A Schematic representation of screw-fed extruders: (A) axial extruder and (B) radial extruder.

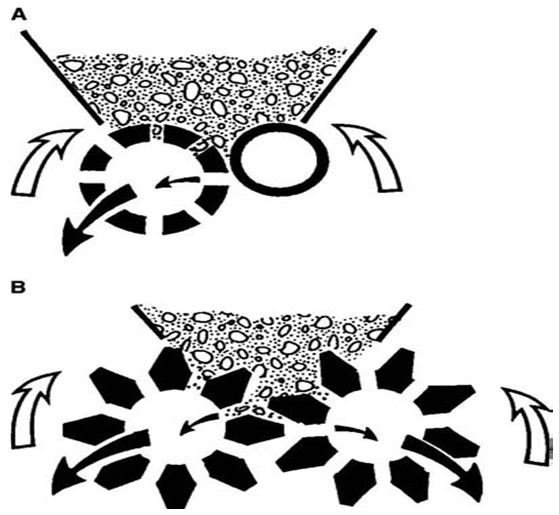

Gravity-fed extruders include the rotary cylinder and rotary gear extruders, which differ primarily in the design of the two counter-rotating cylinders (Fig.4). In the rotary-cylinder extruder, one of the two counter-rotating cylinders is hollow and perforated, whereas the other cylinder is solid and acts as a pressure roller. In the so-called rotary-gear extruder, there are two hollow counter-rotating gear cylinders with counter-bored holes.

Figure 2.3.B Schematic representation of gravity-fed extruders: (A) rotary-cylinder extruder and (B) rotary-gear extruder.

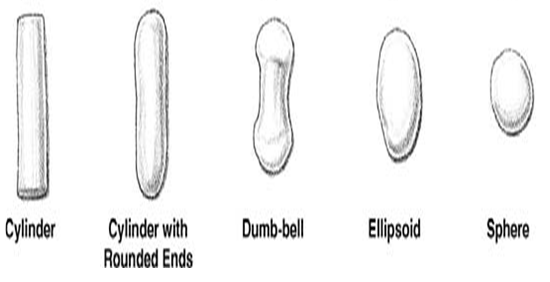

Figure 2.3.C Mechanism of spheronization. transition from cylindrical particles into cylindrical particles with rounded edges, dumbbells, ellipsoids, and spheres.

2.4 Spray Drying and Spray Congealing

Spray drying and spray congealing, known as globulation processes, involve atomization of hot melts, solutions, or suspensions to generate spherical particles or pellets. The droplet size in both processes is kept small to maximize the rate of evaporation or congealing, and consequently the particle size of the pellets produced is usually very small.

During spray drying, drug entities in solution or suspension are sprayed, with or without excipients, into a hot air stream to generate dry and highly spherical particles. As the atomized droplets come in contact with hot air, evaporation of the application medium is initiated. This drying process continues through a series of stages whereby the viscosity of the droplets constantly increases until finally almost the entire application medium is driven off and solid particles are formed. Generally, spray-dried pellets tend to be porous.

During spray congealing, a drug substance is allowed to melt, disperse, or dissolve in hot melts of waxes, fatty acids, etc., and sprayed into an air chamber, where the temperature is below the melting temperatures of the formulation components, to provide spherical congealed pellets under appropriate processing conditions. A critical requirement in a spray congealing process is that the formulation components have well-defined, sharp melting points or narrow melting zones. Because the process does not involve evaporation of solvents, the pellets produced are dense and non-porous.

2.5 Cryopelletization

Cryopelletization is a process whereby droplets of a liquid formulation are converted into solid spherical particles or pellets by using liquid nitrogen as the fixing medium. The procedure permits instantaneous and uniform freezing of the processed material owing to the rapid heat transfer that occurs between the droplets and liquid nitrogen. The pellets are dried in conventional freeze dryers. The small size of the droplets and thus the large surface area facilitate the drying process.

2.6 Melt Spheronization

Melt spheronization is a process whereby a drug substance and excipients are converted into a molten or semi-molten state and subsequently shaped using appropriate equipment to provide solid spheres or pellets. The process requires several pieces of equipment such as blenders, extruders, cutters (known as pelletizers in the plastics industry), and spheronizers. The drug substance is first blended with the appropriate pharmaceutical excipients, such as polymers and waxes, and extruded at a predetermined temperature. The extrusion temperature must be high enough to melt at least one or more of the formulation components. The extrudate is cut into uniform cylindrical segments with a cutter. The segments are spheronized in a jacketed spheronizer to generate uniformly sized pellets. Depending on the characteristics of the formulation ingredients, pellets that exhibit immediate- or sustained-release characteristics can be manufactured in a single step. The pellets produced are unique in that they are mono-size, a property unmatched by any other pelletization technique. However, the process is still in the development stage, and additional work is needed before the process becomes a viable pelletization technique.

2.7 Spherical Agglomeration

Spherical agglomeration, or balling, is a pelletization process in which powders, on addition of an appropriate quantity of liquid or when subjected to high temperatures, are converted to spherical particles by a continuous rolling or tumbling action. Recent technologies used for spherical agglomeration are rotary fluid-bed granulators and high-shear mixers. Spherical agglomeration can be divided into two categories— liquid-induced and melt-induced agglomerations.

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT articles@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Job Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE

3. Evaluating the Quality of Pellet

The objective of all agglomeration processes is to produce a product with the properties desired. It is therefore important to quantify the physical properties of the agglomerates produced and to relate them to the initial feed properties and the operating conditions. The most common physical characteristics evaluated are; (i) pellet size and size distribution, (ii) spherecity, (iii) friability, (iv) dissolution testing, (v) pellet strength, (vi) bulk density, and (vii) flow properties.

3.1 Size and Size Distribution

The aim of sizing procedures is the quantitative determination of a dimension that can be related to the particle-forming. The size of pellets can be determined using a variety of parameters: particle size distribution, mean diameter, geometric mean diameter, inter-particle range, mean particle width and length.

Particle size analysis by far the simplest and most widely used method is a simple sieve analysis although the more advanced method of computer-aided image analysis has also been reported. A sieving curve can be obtained by plotting the cumulative percent by weight retained by sieve.

3.2 Spherecity

One of the most important characteristics of a pellet is its roundness. Several methods exist to determine the roundness viz.

i. Visual inspection of the pellets and classification into a group,

ii. One-plane-critical-stability (OPCS), being the angle to which a plane has to be tilted before a particle begins to roll, the ratio of the largest and the smallest diameter of a pellet, and

iii. Shape factors calculated by means of the projected area of the pellet and its perimeter measured with computer-aided image analysis.

3.3 Friability

The tendency of the pellets to flake off during handling resulting in the formation of dust is assessed by rotating the pellets in a friabilator for a fixed period of time by use of glass beads to increase the mechanical stress on the pellets.

3.4 Dissolution Testing

The drug release profile from pellets is another main characteristic. Several authors correlated parameters such as hardness, composition and drug loading with the release profiles of a drug but it is difficult to take general conclusions from the published data since the work has been performed on different dissolution systems.

3.5 Bulk Density

The packing characteristics of particles play an important role in determining the physical properties associated with the product of the material. The bulk and tap densities of pellets are determined to gain an idea of the homogeneity of the particle size distribution. The true density of pellets evaluates the porosity of the pellets and can be determined by the displacement with Helium or mercury or by a pycnometer. From a knowledge of the bulk packing density, the available void space Pb can be calculated for the given distribution, since

Pb = Ps (1 - E)

Where Ps is the particle density and E is the voidage or porosity.

One simple method often used is to fill the container or measuring cylinder by pouring the measured weight of the material and noting its volume, which mathematically represented as,

Bulk density = Weight of sample in mg / Volume in mL

3.6 Flow Properties

Several methods are available to measure the extent of inter-particle forces. Such measurements are often employed as an index of flow. The more common methods are the angle of repose and hopper flow measurements. The angle of repose is best suited for particles greater than or equal to 150 μm. In this range, cohesive effects will be minimal. In the fixed-funnel and free standing cone method, a funnel is secured with a tip at a given height above a graph paper placed on a flat horizontal surface. Pellets or granules are carefully poured through the funnel until the apex of the conical pile just touches the tip of funnel; thus

tan θ=H/R

Where θ is the angle of repose, R the radius of the base of cone, and H the distance between the tip of funnel and the base.

4. ENTERIC COATINGS

Enteric coatings form a subgroup of modified release coatings and a simple definition of such a coating would be one that resists the action of stomach acids but rapidly breaks down to release its contents once it has passed into the duodenum. These coatings will come within the definition of ‘delayed release forms’, as specified in the USP.

5. Rationale for Use of Enteric Coatings

i.Prevention of the drug’s destruction by gastric enzymes or by the acidity of the gastric fluid.

ii.Prevention of nausea and vomiting caused by the drug’s irritation of the gastric mucosa.

iii.Delivering the drug to its local site of action in the intestine.

iv.Providing a delayed release action.

v.Delivering a drug primarily absorbed in the intestine to that site, at the highest possible concentration.

The mechanism by which enteric coating polymers function is by a variable pH solubility profile where the polymer remains intact at a low pH but at a higher pH will undergo dissolution to permit the release of the contents of the dosage form.

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT articles@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Job Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE

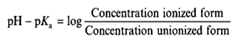

6. Gastrointestinal pH and Polymer Performance

All the enteric polymers in current use possess ionizable acid groups, usually a free carboxylic acid from a phthalyl moiety. The equilibrium between unionized insoluble polymer and ionized soluble polymer will be determined by the pH of the medium and the pKa of the polymer. The Henderson-Hasselbach equation can be used to predict the ratio of ionized to unionized polymer based on these two parameters, i.e.

In order to perform adequately, an enteric-coated form should not allow significant release of the drug in the stomach, yet must provide rapid dissolution of the polymer and complete release of the active material once in the environment of intestine. It is a fact, however, that all of the enteric-coating polymers in the hydrated state in the stomach will be permeable to some degree to a given active material. Formulation measures such as variation of the type and concentration of additions to the film will have an important part to play in keeping this permeability within acceptable limits. Manipulation of performance by variation of the quantity of the applied enteric-coating agent has a powerful part to play here. Variation of this parameter has such a powerful influence that there is a temptation to place almost total reliance upon it in the formulation of an enteric-coated product. Instead, due regard should be given to other formula and process considerations in achieving the minimum effective level of enteric-coating agent.

7. Ideal Enteric Coatings

An enteric coating must possess the general attributes of a non-functional film coating with suitable modifications regarding the pH solubility requirements. A good enteric coating should possess the following qualities;

i. pKa to allow threshold pH of dissolution between pH 5 and 7, ideally between 5 and 6.

ii. Minimal variation in dissolution due to changes in ionic media and ionic strength of dissolution fluid.

iii. Rapid dissolution in non-gastric media.

iv. Low permeability.

v. Ability to accept commonly used plasticizers, pigments and other additives without undue loss of function.

vi. Good response between quantity applied and ability to resist gastric juice.

vii. Capable of being processed from aqueous media.

viii. During processing, the material in solution/suspension should be of low viscosity, not subject to coagulation, non-tacky on application and be aesthetically pleasing in its final coating form. Equipment cleaning should not be unduly complicated.

ix. The enteric-coating material should be stable on storage. Films coated onto tablets or granules should not be subject to performance changes on storage.

x. Adhesion between film and substrate should be strong.

8. Dosage Forms

In general, film-coated dosage forms can be divided into multiple-unit and single-unit dosage forms. Single units comprise tablets and film-coated capsules or other forms, usually monolithic structures. Multiple-unit dosage forms can be packages containing granules, capsules containing pellets, or compressed film-coated particles. In the latter situation, total dosage is divided into multiple units that are dispersed in the GI tract, which often results in safer and usually faster action of the drug.

In 1998, the first tablet containing enteric-coated particles was marketed (Losec MUPS, Omeprazole-Magnesium by ASTRA, Sweden). This is a new principle and may serve as a paradigm of how enteric dosage forms may be designed in the future. However, flexible polymers are required for this purpose, and a variety of other factors have to be considered. In addition to flexibility of the film coating, suitable larger sized filler-binders and stable and strong pellet cores also have to be taken into account. Only the methacrylic acid copolymers seem to have suitable properties necessary to produce these dosage forms.

9. SUMMARY

Enteric coating are performed by drug layering technique using conventional coating pan. This method of pellet formulation is very simple as compared to tedious, time-consuming and costly pelletization techniques viz. extrusion-spheronization, melt-spheronization, Wurster’s technique etc. as it requires simple manufacturing steps as well as pellets produced by this technique are of having good appearance, uniformly rounded, cost saving.

Thus, the delayed-release i.e. enteric-release dosage form of drugs can be successfully formulated using drug layering technology.

In an attempt to develop stable and robust delayed release formulation as enteric coated. The following steps involves

9.1 Physico-chemical properties of API

- Appearance

- Particle size determination

- Solubility profile of drug

|

Descriptive terms |

Approximate volume of solvent in mL per g of solute |

|

Very soluble |

Less than 1 |

|

Freely soluble |

From 1 to 10 |

|

Soluble |

From 1 to 30 |

|

Sparingly soluble |

From 30 to 100 |

|

Slightly soluble |

From 100 to 1000 |

|

Very slightly soluble |

From 1000 to 10 000 |

|

Practically insoluble |

More than 10 000 |

- Assay

9.2 Identification Tests of API

- HPLC analysis

- Melting point determination

- IR spectral analysis

9.3 Formulation Aspect and optimization

9.4 Evaluation Parameters

- Physical description

- Water content

- Drug retainity

- Dissolution profile

- Assay

9.5 Stability Studies

- Accelerated /Common high stress study(Temp./Humidity/Light)

10. REFERENCES

1. J.J. Sousa, A. Sousa, F. Podczeck and J.M. Newton (1996) “Influence of process conditions on drug release from pellets”, International Journal of Pharmaceutics 144. 159-169.

2. Sadeghi, Fatemeh, Ford, James L., Rubinstein, Michael H. and Rajabi-Siahboomi, Ali R. (2000) “Comparative Study of Drug Release from Pellets Coated with HPMC or Surelease”, Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy, 26:6,651 — 660.

3. Bikiaris, Dimitrios and Koutris et. al., “New Aspects in Sustained Drug Release Formulations”, Recent Patents on Drug Delivery & Formulation, Volume 1, Number 3, November 2007 , pp. 201-213(13).

4. Murty and Aruna Mummini (2006) “Evaluation of potential multi-particulate drug delivery systems”, PubMed Central.

5. Claudio Nastruzzi1, Rita Cortesi, Elisabetta Esposito, Alberto Genovesi, Alessandro Spadoni, Carlo Vecchio and Enea Menegatti (2000) “Influence of Formulation and Process Parameters on Pellet Production by Powder Layering Technique”, AAPS PharmSciTech, 1 (2) article 9.

6. R. Fekete, R. Zolko, S. Marton and I. Racz (1998) “Effect of Formulation Parameters on the Characteristics of Pellets”, Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy, 24(11), 1073-1076.

NOW YOU CAN ALSO PUBLISH YOUR ARTICLE ONLINE.

SUBMIT YOUR ARTICLE/PROJECT AT articles@pharmatutor.org

Subscribe to Pharmatutor Job Alerts by Email

FIND OUT MORE ARTICLES AT OUR DATABASE